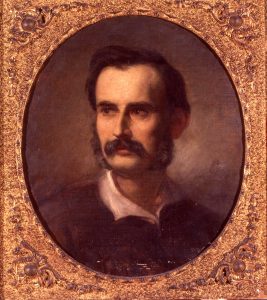

Born in Figueres, the son of a cooper, Monturiol was not the heir and therefore received his early education at the school housed in the Monastery of Vilabertran. By 1834, he was studying a philosophy course in Cervera, which gave access to the university. He probably entered the Faculty of Law, which by around 1835 was already based in Barcelona, though he seems to have abandoned his studies. A decade later, in 1845, he went to Madrid to complete them. However, he never obtained the degree, as his friend, the industrial engineer Damàs Calvet (1836–1891), explained, because Monturiol twice used the money meant for the graduation fees to support charitable causes.

In Barcelona, Monturiol worked as a printer and publisher. He enlisted in the Milícia Nacional (National Militia) during the popular uprisings of 1840–42, fighting, according to Puig Pujadas, in Barcelona, Girona, and Figueres, where his company eventually surrendered. He then went into exile in France for the first time. Years later, Monturiol himself claimed to have taken refuge in Cadaqués in 1841 and 1842.

Following his experience with armed struggle, Monturiol embraced non-violent revolutionary action. He expressed this commitment in an 1844 publication opposing the death penalty and public executions. Around 1846, together with the physician Joan Llach i Soliva (1824–1860?), he appears to have founded a short-lived periodical entitled La Madre de Familia (“The Mother of the Family”), of which eight issues were published, though none have survived. Monturiol later reprinted one of its articles in El Padre de Familia (“The Father of the Family”), a magazine he would publish several years later. In this publication, Monturiol and Llach promoted women’s education, though they conceived of it almost entirely within the domestic sphere.

In 1847, Monturiol launched another weekly, La Fraternidad (“Fraternity”), which reflected his role in developing communisme cabetià (Cabetian communism) in Catalonia and Spain. Étienne Cabet, a French thinker, was at that time promoting a peaceful route to communism through the foundation of a utopian city – Icaria – where social classes would disappear and each person would contribute according to their abilities and receive according to their needs. The success of Icaria, he believed, would inspire other cities around the world to follow its example. Cabet set out his ideas in the novel Voyage en Icarie (Journey through Icaria). In 1847, Cabet began fundraising to finance an expedition to the United States to establish Icaria. The weekly promoted by Monturiol also organised a collection of funds and began publishing a serialised Spanish translation of Cabet’s book. Early in 1848, an expedition of Cabetian followers left Le Havre, among them the physician Joan Rovira i Font (1824–1849), a member of the Barcelona circle.

After the European revolution of 1848, La Fraternidad was shut down and Monturiol was persecuted, though he managed to escape and go into exile in France. Upon his return, he founded El Padre de Familia, a journal promoting socialism, which was closed by court order a year later.

Monturiol combined his political career with work in publishing, while also developing inventions. His first known invention was a system for printing copybooks, devised together with his friend Martí Carlé (1818–1897).

Algú considera que el seu projecte fou concebut ja el 1848, però prengué forma el 1856. En el seu projecte Monturiol demostra conèixer les nombroses experiències sobre navegació submarina que dataven del Renaixement. S’adonà que el coneixement dels materials i les tècniques del seu temps permetien dissenyar una nau submarina pràctica. Monturiol l’anomenà “Ictíneo”, nau-peix, que Carles Rahola traduí per “Ictineu”.

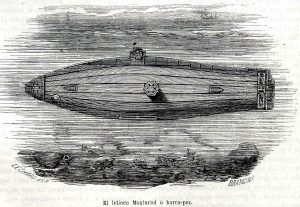

One of Monturiol’s most ambitious projects was a system for underwater navigation, apparently inspired by witnessing the hardships endured by coral fishers in Cadaqués – and also by the prospect of great profit. Some have suggested that he conceived the idea as early as 1848, though it only took shape in 1856. In his project, Monturiol demonstrated knowledge of the many attempts at submarine navigation dating back to the Renaissance. He realised that the materials and techniques available in his day made it possible to design a practical submersible vessel. He called it the “Ictíneo” – from the Greek for “fish-ship” – translated by Carles Rahola into Catalan as “Ictineu”.

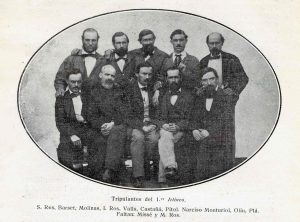

In October 1857, Monturiol promoted the creation of a company to finance the construction of a submarine and to profit from its possible applications. The shareholders were mainly artisans and tradesmen from the Empordà region. With their support, Monturiol set up a workshop in the Port of Barcelona, leading a team of around a dozen people, including master shipwrights, carpenters, mechanics, boilermakers, and locksmiths. They built a prototype that was not ready until the summer of 1859. The June trials were unsuccessful, but in September the test Ictíneo successfully demonstrated underwater navigation in the Port of Barcelona.

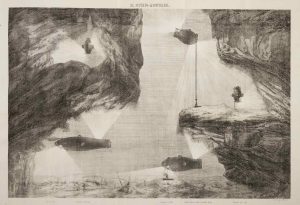

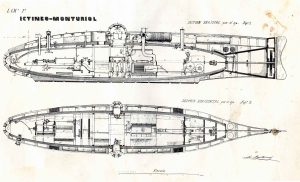

The Ictíneo had a double hull: an outer, fish-shaped one and an inner, cylindrical one. The double hull allowed it to submerge to considerable depths, while the fish-like shape improved hydrodynamics. The inner hull housed the machinery, crew, manual propulsion system, and the necessary instruments, as well as a device to renew the air inside. Between the two hulls were the ballast tanks, designed to assist surfacing, and a submersion system that Monturiol modelled on a swim bladder.

In 1860, trials were carried out before the Spanish Navy at the Port of Alacant. The resulting reports were not particularly favourable, but the government offered Monturiol the use of a naval shipyard to build a larger Ictíneo. Monturiol and his collaborators declined the offer and created a new company to finance the project, raising funds not only from shareholders but also through public events, thanks to the growing public interest in the invention. In 1862, they launched the larger Ictíneo at the Port of Barcelona. However, the tests revealed limitations, such as inadequate speed. To address these issues, the team made various modifications and decided to incorporate a steam engine capable of operating with a fuel compatible with life inside the vessel. By late 1867, they had conducted several underwater navigation trials powered by steam, without doubt a pioneering achievement worldwide.

Nevertheless, the Ictíneo failed to generate profits, and the company declared bankruptcy at the end of 1867. Around 100,000 pesetas had been invested in the first prototype between 1857 and 1862, and approximately 400,000 more in the full-scale model between 1862 and 1867. In 1868, the Ictíneo was dismantled to pay off debts, marking the end of a decade devoted to submarine navigation. During this period, Monturiol wrote a treatise on his work – the first in history – which was published posthumously in 1891 and remained unique for many years. It should be noted that Monturiol did not consider military applications a priority; rather, he envisioned the Ictíneo as a means for harvesting coral and recovering shipwrecks, which he believed would make the vessel profitable. This lack of emphasis on military use explains why his work was made public.

During the Sexenni Revolucionari (Revolutionary Six-Year Period), Monturiol played a prominent role. He was elected deputy to the Corts Constituents (Constituent Assembly) of 1874, and, once in Madrid, he was appointed director of the Fábrica Nacional del Sellol (National Stamp Factory). In this capacity, he was responsible for printing the stamps of the new Spanish Republic and is thought to have incorporated some of his own innovations, such as a more effective adhesive. The Republic, however, was overthrown in January 1874 by a coup d’état. Monturiol remained in Madrid for several months to pursue matters of public interest, including offering the army a portable cannon of his own design for use against the Carlists.

He later returned to Barcelona, where he worked in the office of a banking institution and continued his activities as a journalist, writer, and inventor. Among his projects, he is believed to have developed a chemical process for preserving meat. He also remained active in the republican movement, now as a member of the Partit Republicà Possibilista (Possibilist Republican Party) led by Emilio Castelar (1832–1899), one of the four presidents of the First Spanish Republic.

The Museu Marítim (Maritime Museum) preserves texts of Monturiol’s popular science lectures delivered to various republican associations in Barcelona. In 1885, he is believed to have contracted cholera during an outbreak that affected the city. His daughter Anna took him into her home in Sant Martí de Provençals, where he died. As a final note, the civil governor of the province of Barcelona attempted to prevent the republican groups from holding tributes in his honour, but these were ultimately carried out.

Works

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Un reo de muerte: las ejecuciones y los espectadores: consejos de un padre a su hijo. Barcelona, Imprenta de Tomás Carreras, 1844. [Edición facsímil en RIERA, 1986].

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Un reo de muerte: las ejecuciones y los espectadores: consejos de un padre a su hijo. Barcelona: Imp. de Tomás Carreras, 1844. [Facsimile edition in Riera, 1986.]

- La Madre de Familia, 1846. Weekly co-written with Joan Llach i Soliva. None of the eight known issues on Puig Pujadas (1918) have survived.

- La Fraternidad, 1847-1848.

- CABET, Étienne. Viage por Icaria. Barcelona: Imprenta y Librería Oriental de Martín Cerlé, 1848 [1856], 504 pp. Translation by Francisco Orellana (up to p. 144) and N. Monturiol.

- El Padre de Familia 1849-1850.

- M. MONTURIOL, Narcís. Reseña de las doctrinas sociales antiguas y modernas. Barcelona: Imprenta de Juan Capdevila, 1850, 112 pp.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Proyecto de navegación submarina. El Ictíneo o barco-pez. Barcelona: Imp. de Narciso Ramírez, 1858.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Memoria sobre la navegación-submarina, por el inventor del Ictíneo o barco-pez… Barcelona: Est. Tip. de Narciso Ramírez, 1860.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Monturiol a la prensa periódica. Madrid 16 de mayo de 1861, viii pp., no place indicated.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. A la prensa periódica: a propósito de la construcción de un ictíneo de guerra. Barcelona: Impr. Narciso Ramírez, 1862, 8 pp.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. El Ictineo y la Navegación submarina. Barcelona: Imp. de Narciso Ramírez, 1 January 1863, 6 pp.

- NAVEGACIÓN SUBMARINA. SOCIEDAD EN COMANDITA. Proyecto de una sociedad comanditaria titulada la navegación submarina. Barcelona: I. López, 1864, 30 pp.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís; CLAVÉ, Josep Anselm [selected from various authors]. “Almanaque y Calendario”, Almanaque democrático para el año (bisiesto) de 1864, pp. 17-32.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. “El océano”, Almanaque democrático para el año (bisiesto) de 1864, pp. 86-97.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís; CLAVÉ, Josep Anselm; SUNYER CAPDEVILA, Francesc; ALTADILL, Antoni; TUTAU, Joan; TORRES, Josep Maria. “Los autores del Almanaque Democrático a sus conciudadanos”, Almanaque democrático para 1865, pp. 14-18.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. “Una idea del Universo en relación con el hombre”, Almanaque democrático para 1865, pp. 26-33.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. A los interesados en el Ictíneo y a cuantos han contribuido a su desarrollo. Barcelona: Imp. Narciso Ramírez, 6 February 1866.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Memoria leída por el Gerente industrial de la Navegación Submarina en la Junta General del 22 de abril de 1866. Barcelona: Imp. de Narciso Ramírez, 1866, 16 pp.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. La Navegación Submarina. Memoria leída por el Inventor del Ictíneo en la Junta General de 8 de Diciembre de 1866. Barcelona: Imp. de Narciso Ramírez, 1866.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. La Navegación Submarina. Memoria leída por el Inventor del Ictíneo en la Junta General de 12 de Enero de 1868. Barcelona, no imprint, 22 pp.

- LANDA, Juan; MONTURIOL, Narcís.. Hombres y mujeres célebres de todos los tiempos y de todos los países: biografías de personajes ilustres. Barcelona: Seix y Compañía, 1875-1877, 2 vols. (634 pp., [22] leaves of plates; 752 pp., [20] leaves of plates). Monturiol authored six biographies in the first volume and virtually all of the second.

- MONTURIOL, Narcís. Ensayo sobre el arte de navegar por debajo del agua. Barcelona: Imp. de Henrich y Cia, 1891. (Facsimile edition, Barcelona: Alta Fulla, 1982; Catalan version by Carles Rahola, Barcelona, Mancomunitat de Catalunya, 1919; facsimile, Barcelona, Edicions científiques catalanes, 1986; HTML format: https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/ensayo-sobre-el-arte-de-navegar-por-debajo-del-agua–0/ ).

Archival sources

- Museu Marítim de Barcelona https://www.mmb.cat/colleccions/navegacio-submarina/

- Museu de l’Empordà, Figueres (paintings, portraits, publications)

- Biblioteca Nacional de Catalunya, Barcelona (family correspondence c. 1860–1882)

Main References

- ESTRANY, Jerónimo, Narciso Monturiol y la Navegación Submarina. Juicios críticos, Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1915. Available at: https://issuu.com/juaneloturriano/docs/48_78

- RIERA TUÈBOLS, Santiago, ‘Los “Ictineos” de Narcís Monturiol’, Investigación y Ciencia, 1981, no. 59 (August), pp. 99-108.

- RIERA TUÈBOLS, Santiago, Narcís Monturiol. Una vida apassionant, una obra apassionada, Barcelona, CIRIT, Generalitat de Catalunya, 1986.

- ROCA ROSELL, Antoni (coord.). Narcís Monturiol. Una Veu entre utopia i realitat = Una voz: entre utopía y realidad. Barcelona: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, 2009. Includes contributions by Anna Capella, M. Lluïsa Faxedas, Jaume Guillamet, Guillermo Lusa, Carles Puig Pla, Enric Pujol, Antoni Roca Rosell, Francesc Roca, and Emigdi Subirats.

- ROCA ROSELL, Antoni. ‘Monturiol i el seu taller al port de Barcelona’. In Patrimoni portuari, Associació del Museu de la Ciència i de la Tècnica i d’Arqueologia Industrial de Catalunya (AMCTAIC), Museu de la Ciència i de la Tècnica de Catalunya, Museu del Port de Tarragona, Port de Tarragona, Tarragona, 2020, pp. 297–306. Available at: https://www.amctaic.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/XI_Jornades_Arqueologia_Industrial_de_Catalunya.pdf

- ROCA ROSELL, Antoni. ‘La navegación submarina, un reto apasionante.’ In SILVA

- SUÁREZ, Manuel (ed.), El Ochocientos. De las profundidades a las alturas, Técnica e ingeniería en España VII. Zaragoza: Real Academia de Ingeniería, Institución “Fernando el Católico”, Prensas Universitarias de Zaragoza, 2013, vol. VII-I, pp. 785–839.STEWART, Matthew. Monturiol’s Dream. London: Profile Books, 2003. Spanish version: El sueño de Monturiol. Madrid: Taurus, 2004. Catalan version: El somni de Monturiol. Barcelona: Graó, 2009.