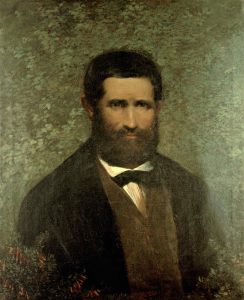

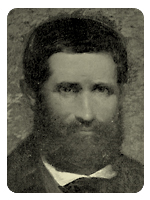

Joan Isern was born in Can Batlló de Setcases, in the extreme NW of the Camprodón Valley (Ripollès), on September 25, 1821. As a child and while accompanying the shepherds in the mountain emprivos during the summer months, he had the opportunity to observe the herbalists who came to make sheets of medicinal plants and to meet the botanists who year after year went to herborize. Isern studied for the first time literature with Mosén Prats, vicar of Camprodón who, telling that Can Batlló held the chaplaincy of Villalonga de Ter, oriented him towards the Girona seminary although, when the good weather arrived, when he returned home to collaborate in the work farmers and ranchers, he used to guide foreign botanists who requested his assistance given the knowledge of the plants that the young Isern was developing and the knowledge he acquired of the mountain range beyond the border with Aragon.

Among those scientists were the Englishman Philip Barker Webb and the Italian Pietro Bubani who advised Isern to continue studying Botany at the Barcelona Lonja Schools. For this reason, he asked the parish priest of the seminary to be transferred to the Lonja in the Catalan capital where during the first year he was a student of a young Miguel Colmeiro Penido. Determined to pursue a scientific career rather than an ecclesiastical one, the following year Isern returned to Girona to study, at the Provincial Institute, the subjects that he lacked in order to gain access to medicine because, in accordance with the Pidal plan of 1845, the teachings of seminaries no longer automatically accredited for civilian careers. In Girona, Isern, after studying the subjects that he could not validate, took the grade exam so that the following year he returned to Barcelona to continue his higher studies. During that time, Isern earned his living by collecting and selling medicinal herbs and helping a peasant from the Sant Bertran orchards with the farm work, since, his parents having died, the heir to Can Batlló considered himself free from the economic clauses established by the great-grandparents at the time of the constitution of the chaplaincy of Villalonga due to the fact that his brother had resigned from the priesthood.

During the 1849-50 academic year, in which Isern was taking the second year of Medicine, although he was already recognized for his knowledge of phytology, instructions were sent from Madrid to all the Spanish universities so that they could propose candidates to fill the post of collector botanist at the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid, a position for which a bachelor’s degree was not required. The professors of the University of Barcelona, led by the rector, proposed the name of Joan Isern, who was appointed to occupy it when, at the end of the following year, the General Directorate of Public Instruction authorized the director of the Madrid Museum to appoint a collector ‒ with a salary of five hundred reales (the Spanish currency of that time) each month, firewood and accommodation apart‒ Joan Isern left to Madrid on July 3, where he carried out the functions of collector and curator of the Museum and Royal Botanical Garden throughout the decade (from 1857 his official status was that of teaching assistant and head of the library).

Recognized his expertise for the identification and preparation of vegetables, he was called to participate in herborization campaigns in the Montes de Toledo, Guadalajara, Almeria (Sierra de los Filabres), etc. At the same time, Isern was still studying medicine, obtaining his bachelor’s degree in 1854. However, his studies were a source of headaches. Not because of the difficulty that the different subjects could present him with, but because of the clash with the bureaucracy that often did not allow him to take the exam when, due to the obligation to serve the professors of botany at the Museum, he was deprived of attending class, a requirement considered essential to qualify for examination. At that time, the repression that followed the popular revolt of the Vicalvarada of 1854, in which Isern had participated, caused another academic scare. Joan Isern married the following year Tomasa del Olmo Soto, whom he had met in Valdemoro where he contracted cholera, a disease that he had decided to fight in that Madrid town when, having gone to herborize, the epidemic of 1854 broke out there.

At the beginning of the 1860s, the attempts, long incubated, by the Elizabethan governments to send a military mission with neo-colonial overtones to the Pacific finally came to fruition, to which, at the initiative of the Directorate of Public Instruction of the Ministry of Public Works, it decided to add at the last minute a scientific commission, the so-called Scientific Commission of the Pacific (or CCP), of which Isern ‒then already a family man‒ was appointed (the only) botanist helped both by the reputation as an expert and a hard-working man that he had earned freehand as well as through the good offices of one of its main supporters, the zoologist Mariano de la Paz Graells de l’Agüera, who continued to be very influential in Madrid circles.

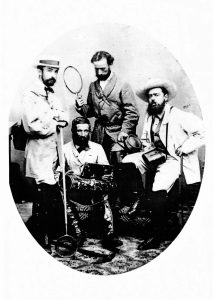

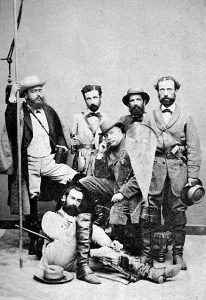

The scientific commission ‒chaired by Patricio Paz Membiela, a retired sailor who is fond of malacology‒ was made up, together with Isern, of the naturalists Manuel Almagro Vega, Fernando Amor Mayor, Marcos Jiménez de la Espada Evangelista, Francisco Martínez Sáez and Bartomeu Puig Galup, together with the photographer and cartoonist Rafael Castro Ordóñez. On August 10, 1862, the expeditionary scientists embarked, in Cádiz, on the navy ships. It can well be said that it is doubly so because the subordination to military objectives, and in particular to the authoritarian command of the captain of the ship in which they were traveling (the frigate Triunfo, 70 meters long and with a crew of close to five hundred men) and of General of the fleet, seriously hindered the work of the members of the CCP by limiting their mobility, always subject to the discretion of others, as Isern and the other scientists experienced from the first stopover in Tenerife where they were not allowed to explore the Teide area. However, Isern was able to grow herbs in the surroundings of Santa Cruz and, notably, in the primeval forest of Las Mercedes.

The disagreements did not end during the Atlantic crossing, nor in Brazil, nor once the eight expeditionaries met again on the Pacific coast, as far as Isern arrived by land ‒together with Paz, Amor and Almagro‒ after crossing the Río de la Plata and the Pampas and cross the Cordillera from Mendoza to the Chilean Santa Rosa. Once in Chile, Isern and Almagro undertook long and important exploration campaigns that took them, together, but also separately, to Bolivia and Upper Peru. Finally, in mid-1864, the paths of the sailors and those of the CCP scientists – who were forced to disembark and invited to return to Spain on their own – definitively diverged. The voyages of the Navy ships, on a mission that became a war mission, have left their mark on the gazetteer of the Spanish capital: Callao, Abtao…, as a result of the bombings and other acts of war that they carried out.

Instead, four of the scientists –Almagro, Jiménez de la Espada, Martínez and Isern (Amor had died; Paz had resigned and the other two disassociated themselves)– decided to continue the exploratory assignment after obtaining their permission (and little else) from the civil authorities of Madrid to undertake what they called the Great Journey: nothing less than the integral crossing of Amazonian America to study its nature. From coast to coast, from Guayaquil to Pernambuco, they followed an itinerary – for a large part of which there were not even bridle paths – that from Quito led them to the heart of the Oriente Province of Ecuador: Papallacta, Baeza, Archidona… until they found the navigable rivers that, with the help of the rafts in which the indigenous people were convoying them, allowed them to reach the Amazon and finally reach Greater Pará and Pernambuco from where, on November 30, 1865 (more than a year after leaving Guayaquil) embarked to Lisbon. The intrinsic difficulties of that heroic expedition, added to the economic hardships with which they carried it out, damaged the health of the naturalists, especially that of Isern, who died in Madrid at the end of January 1866, a month after having finally arrived.

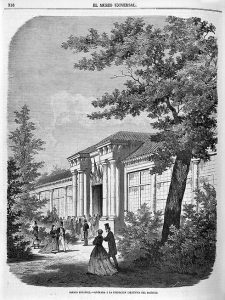

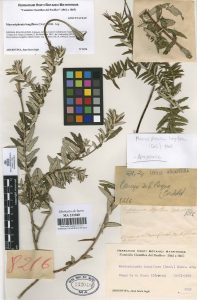

Except for a public exhibition of the objects that the members of the CCP had been sending during the trip, an exhibition that was held that same 1866 in the Botanical Garden of Madrid, a good part of those materials (on the order of one hundred thousand samples of nature and of American cultures) were left unchecked or, in some cases, loosely scattered among schools. Fortunately, the Isern herbarium was preserved despite having also been shelved for a long period. Actually, it took many years before it began to be studied. The collection assembled and sent by Isern was enormous (no other member of the CCP surpassed him in dedication): thousands of exsicata rigorously prepared and accurately annotated, often preserved with a titanic effort from infestation or the inclement meteors of the humid jungles. Specimens of about eight thousand different plant species, of which nearly six thousand were collected by Isern itself, from the Canary Islands, Cape Verde, Brazil, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador and again Brazil, some of these last ones in painful circumstances when from Tabatinga the botanist’s health had already deteriorated.

The bulk of this American herbarium is currently preserved in the Royal Botanical Garden of Madrid, although, in fact, the cataloging did not advance until, in the 1930s, Ignacio Bolívar Urrutia, then director of the Garden, created the section of tropical botany, putting in front an outstanding botanist: Josep Cuatrecasas Arumí, son of Camprodón, who, with a scholarship from the Board for Extension of Studies, traveled to Berlin and promoted the publication of the first results of the analysis of a part of that herbarium (Cuatrecasas, 1935; Sleumer, 1936, and Trelease, 1941). However, Cuatrecasas – who during the Spanish war had held the position of director of the Botanical Garden – had to go into exile and his studies were once again interrupted. In 1958, an agreement with the Darwinion Institute of Botany (San Isidro, Argentina) allowed the study of Argentine plants, while in 1978 and through another agreement, in this case with the Gothenburg Botanical Museum, the study of Ecuadorian plants. Lastly, during the eighties, researchers from the Botanical Garden, and notably the botanist Paloma Blanco Fernández de Caleya, concluded the cataloging and assembly of the imposing Isern collection, currently made up of some twenty-five thousand herbarium sheets. There are also Isern plants in the Department of Botany at the University of Girona (from the herbarium that he collected, commissioned by the director, when he was a student at the Girona institute), or also in the Botanical Institute of Barcelona, in the herbarium of Mariano de la Paz Graells in San Lorenzo del Escorial, and in the Webb herbarium of the Botanical Institute of Florence.

Written by

Josep Cuello Subirana, doctor in biology and writer.

– – –

References

*profiles of Joan Isern:

- Ametller, J. Necrología de Don Juan Isern y Batlló. El Pabellón Médico VI, 134-136, 146-148 i 157-162. Madrid, 1866.

- Graells, M.P. Necrología: el botánico español D. Juan Isern. La Gaceta de Madrid, April 30, 1866.

and also:

- Perals, J. Joan Isern Batlló Carrera (1821-1866) in http://www.setcases.org

- Rodríguez Veiga Isern, P. Juan Isern Batlló y Carrera (1821-1866) in https://www.madrimasd.org/cienciaysociedad/patrimonio/personajes/

*diaries of the members of the Scientific Commission (published by others, except Almagro’s):

- Almagro, M. La Comisión Científica del Pacífico. Viaje por Sudamérica y recorrido del Amazonas. Madrid, 1866. There is a facsimile edition published by Laertes (Barcelona, 1984).

- Barreiro, A.J. Diario de la Expedición al Pacífico llevada a cabo por una comisión de naturalistas españoles durante los años 1862-1865, written by D. Marcos Jiménez de la Espada. Madrid, 1928.

- Calatayud Arinero. M.A. Diario de Don Francisco de Paula Martínez y Sáez. Miembro de la Comisión Científica del Pacífico (1862-1865). Madrid, 1994.

- Blanco Fernández de Celaya, P. and D. and P. Rodríguez Veiga: El estudiante de las hierbas. Diario del botánico Juan Isern Batlló y Carrera (1821-1866). Madrid, 2006.

*studies and chronicles on the Pacific Scientific Commission:

- Barreiro, A.J. Historia de la Comisión Científica del Pacífico (1862-1865). Madrid, 1926.

- Miller, R. R. For Sience and National Glory. The Spanish Scientific Expedition to America, 1862-1866. University of Oklahoma Press, 1968 (Spanish translation: Por la ciencia y la gloria nacional… Barcelona ‒Ed. del Serbal‒, 1983).

- Puig-Samper, M.A. Crónica de una expedición romántica al Nuevo Mundo. La Comisión Científica del Pacífico (1862-1866). Madrid, 1988.

*about the Isern herbarium:

- Blanco Fernández de Caleya, P. and D. Rodríguez Veiga. “Comisión Científica del Pacífico (1862-1866)”: Estado actual del Herbario Isern en el Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid. Boletín Real Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat, no. extraordinary 125th anniversary. Madrid, 1996.

- Cuatrecasas Arumí, J. Plantae Isernianae, I. Anales de la Univ. de Madrid (Ciencias), 1935.

- Sleumer, H. Plantae Isernianae, II. Ericaceae. Trabajos Museo Nac. Ci. Nat. Jard. Bot, 32, (1936), but also Flacourtiaceae (1980) and Olacaceae (1984) both published in Flora Neotropica.

- Trelease, W. Plantae Isernianae, III. Piperaceae. Ciencias (Mexico) 2, 5, 1941.

*historical novel:

- Cuello Subirana La capsa de Dillenius. Barcelona, 2020.